The work of the immigrant

2024

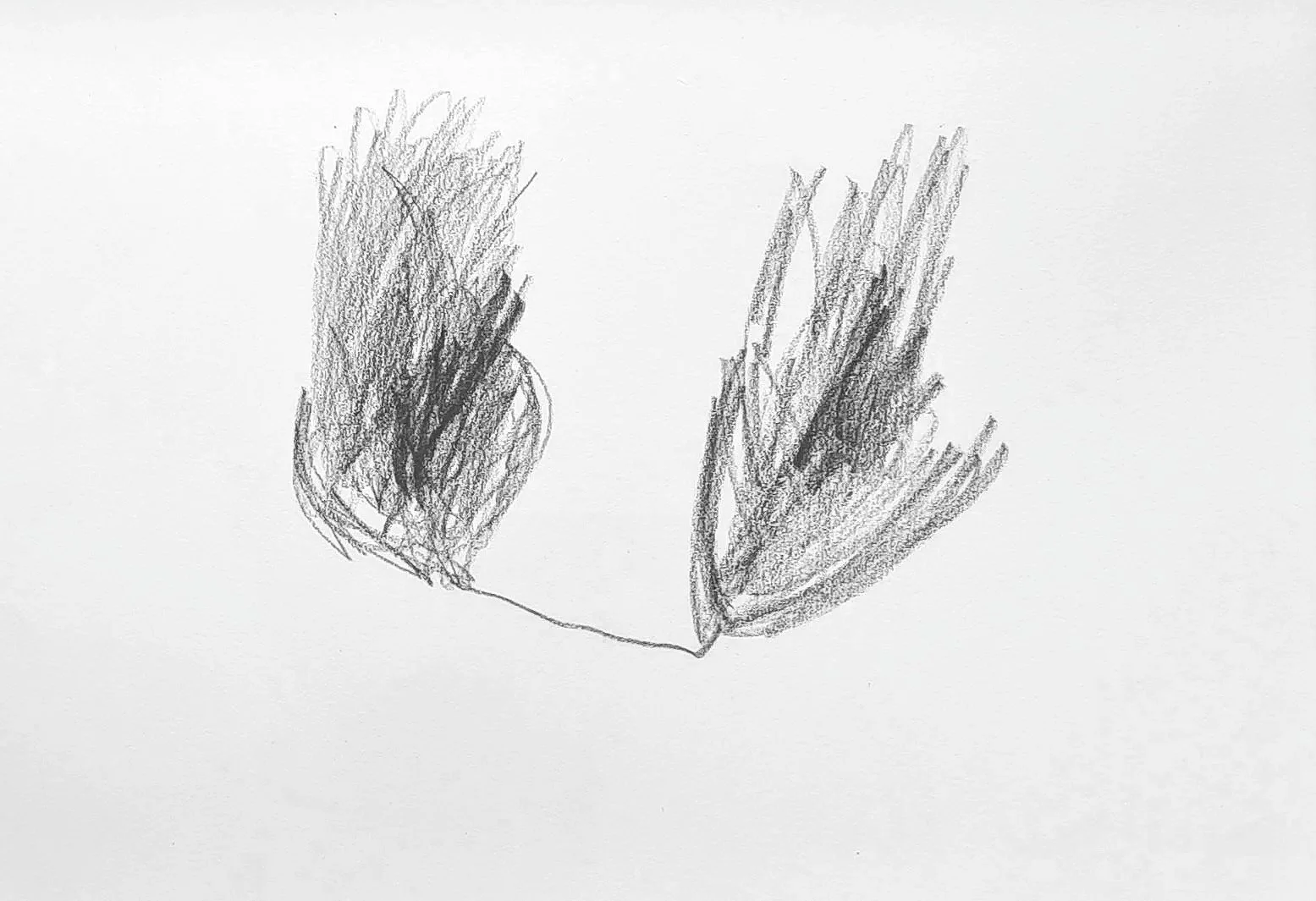

After moving to Denmark, I started working on a series of drawings and a text about the experience of the immigrant, based on an overheard conversation, and a text. This is the beginning of this work which has since then expanded.

1. The immigrant has nothing to lose, but everything to learn. The way they learn is sometimes through pain, other times - through joy. They know that what is easy for the natives must be hard for them. But the immigrant also knows that what the natives take for granted, they can find appreciation for. It's sometimes so deep that it connects to what they love most: they often wish they could show something marvelous in their new country to a friend or a parent back home. The immigrant is a learning specialist - it is what is giving them a roof over their heads. They are a professional student.

They, however, will often always feel like there is something just out of reach, just outside of their ability to learn. They have trained their eyes so sharply to see what can be learned, that because of it they will always find new things to get to know. Something always remains hidden, unknowable. That's why the immigrant puts such an emphasis on education for their child. They know that the unlearnable is too far away for them, but they hope that their child will possess it.

The unlearnable is a sense of ease and belonging fully in their new home.

2. I went for a long walk in the evening. I marveled at the light, so strange compared to both my home country and the other country I called home for some years. In these early days of moving here, something was awakened in me. Coming to a city that prefers bikes over cars, I was struck by the volume of its living heart. It was still pulsating with a symphony of bells, brakes, and pedals, but the hum was much lower than any city of cars. I could feel my own heart slow down to a comfortable beat. The anxiety of unnecessary noise was something to leave behind for when I returned to my other country. Just like my mother tongue. On that walk, I saw two men on bikes, and in the silence of the street I could hear clearly that one of them was saying to the other in English with an accent I couldn’t place: “When you travel to work, this is called your commute”. Their conversation, in which one was sharing his knowledge, and the other was receiving it, put me at ease. I kept thinking about it over the next few days, as if the phrase was something much more than a definition.

3. The dictionary of the immigrant is an unfinished house. It’s a place to live, but also it is a project that you never can abandon, and you somehow never stop thinking about.

4. In the first months, I felt I always met people whose lives became richer when they came here. Both financially and internally – I saw many people who were able to pursue their interests and so-called “passions”. I heard many stories of boring jobs left behind only to open space for new explorations.

5. In time, and with my own experience, I realized that this came from a necessity rather than adventure. For many of us, a lot of our work “before” is as if not important. As if it happened in a child’s play, because it happened elsewhere. My Danish teacher gave me some homework, and it involved reading a dialogue in which two colleagues are talking. One of them immigrated here with his wife. He explains that she has a store for children’s clothing. “Oh?”, says the other, and the first explains: “She couldn’t get a job as an economist which was her work before”. The Dane expresses regret about it, but his colleague insists: “She likes it, so…”.

6. In time, many of us will succeed; but to do so, we would have to change our definition of success. At the airport, the day I moved here, I pulled out my ID card for passport control and I half expected someone to yank me by the collar just before it was my turn at the desk, asking: “Where to?!”. It felt too easy, flying over here, collecting my bags, starting my life. I didn’t know the way the yank would happen is incrementally, over many months.

7. Like a secret club, some words – like passwords – are exchanged only between immigrants. I can’t repeat them here, or I would break a code.

8. Almost a year ago I showed what became the beginning of this text to a close friend. I’ve always been grateful to receive his opinion throughout the many years I’ve sent him almost everything I write. What he said was that he if I add a poetic image to the text, it would make it even more complete. I perhaps couldn’t find the right image, but it is true that ever since I wrote this text, I began – for the first time in my life – a habit and a ritual of writing poetry. I used to think poetry isn’t for me (or I’m not for it).

9. I have been writing this text for many months now, even if it’s less than two pages. Today, I fed it to an AI language model, asking what a fitting last paragraph would be. It told me that speaking about the bridges I have built with friends in both immigrant and local communities would be ideal, with a focus on how I managed to learn the language, find a fitting career, and slowly build a sense of deep belonging in my new home. In this form, AI is a collection of other people’s ideas and language, from which meanness has been edited out as to make it seem suitable for all. As such, it gives me the usual expectation of the immigrant, from which superficial judgment has been removed. The expectation (the hope, the pressure?) is that it turns into a story of completion, that the grey areas are turned into solid blocks of shining white.